|

SAN DIEGO, Aug. 3, 2022 /PRNewswire/ -- Socioeconomic deprivation, including neighborhood disadvantages and persistent low wages, are associated with higher dementia risk, lower cognitive performance and faster memory decline, according to several studies reported today at the Alzheimer's Association International Conference® (AAIC®) 2022 in San Diego and virtually.

Socioeconomic status (SES) — reflecting both social and economic measures of a person's work experience, and of an individual's or family's economic access to resources and social position — has been linked to both physical and psychological health and well-being. Research examining its impact on cognition is growing, and key findings presented at AAIC 2022 include:

- Individuals who experience high socioeconomic deprivation — measured using income/wealth, unemployment rates, car/home ownership and household overcrowding — are significantly more likely to develop dementia compared to individuals of better socioeconomic status, even at high genetic risk.

- Lower-quality neighborhood resources and difficulty paying for basic needs were associated with lower scores on cognitive tests among Black and Latino individuals.

- Higher parental socioeconomic status was associated with increased resilience to the negative effects of Alzheimer's marker ptau-181, better baseline executive function and slower cognitive decline in older age.

- Compared with workers earning higher wages, sustained low-wage earners experienced significantly faster memory decline in older age.

"It's vital we continue to study social determinants of health related to cognition, including socioeconomic status, so we can implement public health policies and create community environments that can improve the health and well-being of all," said Matthew Baumgart, vice president of health policy at the Alzheimer's Association.

At the recent Alzheimer's Association Promoting Diverse Perspectives: Addressing Health Disparities Related to Alzheimer's and All Dementias conference, researchers gathered to share knowledge and drive collaboration on vital health equity issues, including social determinants of dementia risk like socioeconomic status.

Researchers are beginning to understand that risk of cognitive impairment and dementia are, to a significant degree, determined by the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age. To better understand how socioeconomic conditions and genetic risk for developing dementia may interact, Matthias Klee, a Ph.D. student in psychology at the University of Luxembourg, and team, collaborated with researchers from universities of Exeter and Oxford to examine data from 196,368 participants' records in the U.K. Biobank whose genetic risk for developing dementia was assessed through risk scores.

With this sample, the researchers investigated the contribution of individual socioeconomic deprivation — such as low income and low wealth — and area-level socioeconomic deprivation — such as employment rates and car/home ownership — to the risk of developing dementia, and compared it with genetic risk for dementia.

Klee and team reported at AAIC 2022 that:

- Both individual socioeconomic and area-level socioeconomic deprivation contribute to risk of dementia; area-level socioeconomic deprivation was associated with increased risk of dementia for those in very disadvantaged neighborhoods.

- For participants with moderate or high genetic risk, greater area-level deprivation is associated with even higher risk for developing dementia, after adjusting for individual-level socioeconomic conditions.

- Analyses with imaging markers indicated that socioeconomic deprivation both on the individual and the area level were linked to higher burden of white-matter lesions, a marker indicating brain aging and damage.

"Our findings point to the importance of the conditions in which people live, work and age for their risk of developing dementia, particularly those who are already genetically more vulnerable," said Klee. "Both individual health behaviors and non-influenceable living conditions are relevant to explain risk of dementia, particularly for individuals with increased genetic vulnerability. This knowledge opens new opportunities to reduce the number of people affected by dementia not only through public health interventions but also by improving socioeconomic conditions through policymaking."

A large body of research has shown that SES can influence the risk of dementia later in life. SES is often studied using years of education and income level as general factors in health research; however, it is not yet understood how subjective indicators, such as perceived neighborhood environment and access to resources, might also play a role in cognitive health.

To understand this relationship better, Anthony Longoria, M.S., clinical psychology doctoral candidate at University of Texas Southwestern, examined perceptions of neighborhood physical environment and perceived SES alongside a measure of cognition (Montreal Cognitive Assessment scores) in 3,858 diverse individuals from the Dallas Heart Study.

The researchers found that lower quality neighborhood resources, poorer access to food/heating and medical care, and exposure to violence were related to lower scores on a commonly used test of cognitive function in Black and Hispanic, but not White participants.

"This is important given that minority groups disproportionately experience economic adversity and neighborhood disadvantage, in addition to being more likely to be diagnosed with dementia and receive less timely care," said Longoria.

Additional data analyses show perceived neighborhood disadvantage and economic status also may affect white matter volume (WMV) and hyperintensities (WMH) in the brain, both of which are associated with dementia risk and vascular factors. Reported lower income and education were associated with higher WMH in the overall sample, and lower trust, access to health care, income, and education were significantly associated with lower cerebral WMV. "Violence" was associated with more WMH in Black women, lower "trust" was associated with lower WMV in Hispanic men, and lower "access to medical care" was associated with lower WMV in White women.

"Scientists and policymakers should emphasize improving neighborhood resources — including safety, access to high-quality food, clean outdoor spaces and health care — when developing public health policies to help reduce community risk of Alzheimer's and related dementias," said Longoria.

Little research to date has examined the impact of socioeconomic conditions on cognitive resilience, including biological markers of neurodegeneration. To study this, Jennifer Manly, Ph.D., professor of neuropsychology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, and team, partnered with participants in a population-representative intergenerational study in New York City to determine whether parental socioeconomic status, as measured by years of education, buffers the association with levels of plasma ptau-181 (a marker of brain aging and Alzheimer's disease). They also studied whether there was an association with changes in memory among middle-aged adults, and whether moderation of Alzheimer's disease and related brain changes is similar across racialized and ethnic groups.

As reported at AAIC 2022, Manly and team found that higher parental socioeconomic status was associated with reduced impact of Alzheimer's marker ptau-181 on memory, language and executive function in their children as they age.

"Evidence from our multiethnic, intergenerational study suggests that early life socioeconomic conditions may promote cognitive reserve against Alzheimer's-related brain changes," said Manly. "These data show how structural and policy-driven investments, such as access to high quality education, have generational implications. Interventions that reduce childhood poverty could narrow Alzheimer's-related disparities."

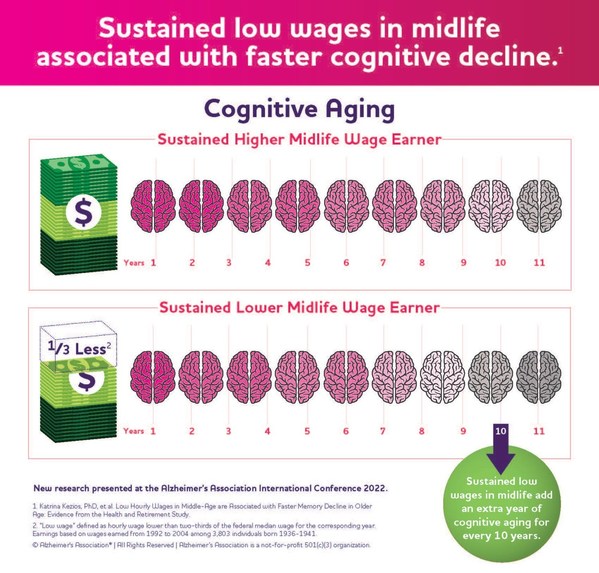

Research into the effects of lower income on health is rapidly expanding. To study whether earning low hourly wages over a long period of time is associated with memory decline, Katrina Kezios, Ph.D., postdoctoral researcher at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, and team, used data from a national longitudinal study of American adults who were working for pay in midlife.

Kezios and team categorized study participants' history of low wages into those who (a) never earned low wages, (b) intermittently earned low wages or (c) always earned low wages, and then examined the relationship with memory decline over 12 years.

The researchers found that, compared with workers never earning low wages, sustained low-wage earners experienced significantly faster memory decline in older age. They experienced approximately one excess year of cognitive aging per 10-year period; in other words, the level of cognitive aging experienced over a 10-year period by sustained low-wage earners would be what those who never earned low wages experienced in 11 years.

"Our findings suggest that social policies that enhance the financial well-being of low-wage workers, including increasing the minimum wage, may be especially beneficial for cognitive health," said Kezios.

The Alzheimer's Association International Conference (AAIC) is the world's largest gathering of researchers from around the world focused on Alzheimer's and other dementias. As a part of the Alzheimer's Association's research program, AAIC serves as a catalyst for generating new knowledge about dementia and fostering a vital, collegial research community.

AAIC 2022 home page: www.alz.org/aaic/

AAIC 2022 newsroom: www.alz.org/aaic/pressroom.asp

AAIC 2022 hashtag: #AAIC22

The Alzheimer's Association is a worldwide voluntary health organization dedicated to Alzheimer's care, support and research. Our mission is to lead the way to end Alzheimer's and all other dementia — by accelerating global research, driving risk reduction and early detection, and maximizing quality care and support. Our vision is a world without Alzheimer's and all other dementia®. Visit alz.org or call 800.272.3900.